what does toot:indexable mean for academic research on the fediverse?

In June 2023, I attended Mastodon: Research Symposium and Tool Exploration Workshop, a two-day workshop hosted by the Centre for Interdisciplinary Methodologies at Warwick University.

During that event there was a day focused on exploring tooling for computational research on the Fediverse, and also a discussion of the ethics involved with that. There were several presentations of tools, many conversations, and even a joint reading and discussion of Research Ethics and the Fediverse by @KatLH@scholar.social.

One thing that became clear throughout the two days is that with the changes at Twitter, it is not only the social network that has been existentially threatened, but also academic practices reliant on Twitter.

Specifically, the practice of doing research based on the creation of datasets from Twitter’s API and the subsequent analysis of those datasets. The loss of API access to Twitter thus fundamentally threatens these practices. There was tangible anxiety about this, as careers, curricula, applications and doctoral thesis plans are built and maintained around these tools and methods.

Just as Twitter users have looked for a Twitter alternative in the Fediverse, so too will those researchers seek an alternative to Twitter-API-style research in the Fediverse.

And, just as those new Fediverse users bring all kinds of behaviours and expectations with them from Twitter to the Fediverse (often causing friction in the process), so too will those researchers bring their research practices and assumptions with them to the Fediverse. And they have already caused friction in the process.

The fundamental thing is that the methods and tools will stay the same, and it’s just the API endpoints that will change. Never mind that behind those end-points are different actors, with different resources, expectations, and needs. I will share three anecdotes that came up during that day that lead me to conclude this.

people do not do the ideal job, but the doable job1

One came from researchers that were both aware of the ethical implications of scraping websites and the fact that this is generally unwanted behaviour in the Fediverse. They were teaching a class on scraping tools for research, and right before the class started… Twitter shut down the API access. So, under pressure of having to teach the class, they went for the Fediverse as a replacement instead, despite being aware of the issues. To me this illustrates how things like time pressure changes one’s calculus and how there are intrinsic pressures to point these tools at something.

The second anecdote, was that several researchers expressed the tension and their frustration between the possibility to automatically pull in large amounts of data on the one hand and the amount of manual work involved with asking or checking consent on the other. In that discussion, people expressed the opinion that it would be “too much work” to do and that the alternative was to either assume consent when data was public or not do this research at all2! Minding the Twitter TOS was one thing, minding potentially 23,000 TOS of Fediverse instances is a whole other. The fact that none of this was machine-readable seemed a blocker.

The third anecdote is that on several occasions the tension between qualitative and quantitative research methods was expressed. Texts like Research Ethics and the Fediverse essentially ask researchers to conduct qualitative research. The quantitative researchers that rely on computational methods of collection and analysis of data, however, argued their methods lead to better science and more valid truth claims. In fact, they would argue that things such as recruiting participants for a study that are not eager to participate (and who technically post publicly) improves the value of the knowledge claims, as it evades self-selection bias. Or that the much larger sample size enabled by such methods provides better insights and, again, less skewing. There are good counter-arguments to these positions, but my interest here is not to unpack the merits of and differences between qualitative and quantitative research. Instead, I want to point out that there will be researchers which will always have good reasons to stick to their ways of working, and calls to change the epistemological foundations of one’s research will not help that much. Or at the very least, it is not enough to rely on.

In addition to these anecdotes, there was a lot of discussion of how one could employ these tools in an ethical and considered ways. People were very eager to do so. Several things came out of those discussions: rate-limiting requests in order not to stress smaller instances; working with opt-in lists such as https://instances.social/ and changing the user-agent of your software to include a link to a page describing the study and ways to opt-out. Finally, there was some consensus that computational methods centred around the measurement of instances is OK as it is the expected pattern in the Fediverse, whereas those centred around users require informed consent from those users. I believe there was agreement on these issues in part because these are very doable things. Rate limiting is just an extra line of code. Speculating on the future, a desire was expressed to have a kind of robots.txt for consenting to be included in research projects. Even the notion of a kind of proxy or clearing house so that individual researchers would not have to seek that consent but could work with ‘pre-approved’ datasets instead was floated.

To summarize, my reading of the issues raised comes down to the following:

- there are pressures, professional or otherwise, to continue a practice honed on Twitter and apply it to the Fediverse, despite ethical considerations

- inconvenience and complexity leads to frustration, and possibly to moral satisfising (“well it is public anyway!”)

- there are fundamental epistemological reasons why people use these methods and which might preclude asking informed consent of individual participants, such as a perceived need for scale.

- These things happen not necessarily because people have nefarious intent, but because they need to do a doable job

I lay out these anecdotes not because I am in support of the views expressed, but to illustrate the ways in which computational research on the Fediverse will happen and continue to lead to friction. Relying on actors doing an ‘ideal’ job when using a system, is bad systems design. Calls for research ethics therefore are not enough. Designers of Fediverse software should consider technical ways of addressing these issues as well. In part, because they set the users of their software up for a mismatch between expectations (“no surveillance!”) and the reality (“the default is to post everything publicly”).

toot:indexable

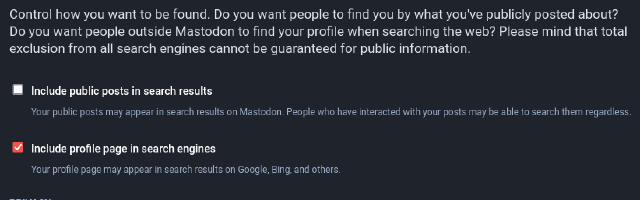

Over summer, I put this discussion on the back of my mind. Reading the pre-release notes of mastodon 4.2 and the new global opt-in for indexability of posts34, however, leads me to think there are some interesting implications for the discussion. The features of 4.2 mean that there will be a machine-readable ‘opt-in’ mechanism for having one’s posts indexed in search functions.

Concerning the ethics discussion, this global opt-in has a few consequences:

First, there is now a much stronger signal that those that do not opt in for search, definitely do not expect their public posts to be scraped for academic research. In addition, servers that do not support this yet should be considered opt-out in any case, despite the visibility status of the post being ‘public’. This flag does not mean that those that do opt-in to search also consent to inclusion in studies, of course. However, there is now a technical and conceptual foundation for flagging consent for inclusion in research, which is something interesting to think about.

Could a future privacy and reach tab in the profile settings also have options about the inclusion of posts for academic research? Could this be something else than a yes or no (“yes, but only anonymized”)?

Of course, such a feature would inherit all the downsides of something like robots.txt: It is not something that is technically enforced, but rather something that relies on cooperation. Nefarious actors can ignore such a flag. In addition, like the use of robots.txt in pen-testing to discover directories that people would rather not have show up in a search engine, an opt-out could be a reason for actors to have a closer look. However, these weak protections are the status-quo already. It sucks, but it is what we have.

On top of that, another downside of such a flag is that informed consent is not something which can be meaningfully given in advance. It needs to be given actively based on information provided. So at the very least there needs to be some mechanism to reach out and provide context (“Your profile showed up in an initial search because you have indicated to agree to have your posts included in academic research. Our study will look at *, if you indeed wish to participate, please respond. Otherwise, we will consider you as opting out.”).

Despite the downsides of such a mechanism, I believe that specifically for academic research, such a flag could be helpful. My main takeaway from the discussions in Warwick is that researchers want to do the right thing, but are constrained in other ways. Crucially such a feature would therefore not be about preventing access by nefarious actors, but rather to help navigate consent for cooperating actors. Hopefully that leads to a better alignment of desires and needs for the different parties involved. At the very least, such a flag could be used to more convincingly demonstrate the lack of consent when taking up disputes.

Scraping on commercial social media has evolved in an antagonistic relationship with the platforms. This antagonism involves finding ways around API limits and around scraping mitigations in an attempt to “unlock” the data held within. In large part, this is because these platforms are proprietary. In the Fediverse the situation is different, the platforms are not proprietary. Rather than a distant and antagonistic relation to the community, researchers should take a collaborative role. For one, they could consider and discuss with the community what such technical ways of addressing consent for research could look like. They could use their access to institutional funds to properly investigate the issue and fund the development of such a feature.

-

“As we know from studies of work of all sorts, people do not do the ideal job, but the doable job.” In Sorting Things Out by Bowker & Star, 1999, p 24 ↩︎

-

Obviously the first position is flawed, already the 2002 version of the AOIR Internet Research Ethics guidelines ask you to consider whether “participants in this environment assume/believe that their communication is private?”, even when it might be technically public. But also the second is flawed, it is possible to do quantitative research and get consent. Its just more work than one may originally have envisaged or lead to believe it should be. ↩︎