Tales From The Vapour Trail

This is a mirror of an article originally published in R&D: a low-end rich media publication. It has been edited to include additional images and captions, as well as to reflect the authors’ improvements in English-language writing since authoring the original in 2016.

Tales From The Vapour Trail

In the computer industry, vapourware is a product, typically computer hardware or software, that is announced to the general public but is never actually manufactured nor officially cancelled.1

One element that all the projects in this publication have in common is that, at some point, they relied on little yellow envelopes magically appearing in the mailbox. Repeatedly receiving small packages that have been sent overseas after ordering products online, made us curious about the possibilities that the source of these packages would offer in terms of making and researching alternative communications technologies. Therefore, we thought it was important for us to visit the People’s Republic Of China and explore the Guangdong province, also known as ’the factory of the world'.

The motivation for the trip was also directly related to working on Meshenger and various other radio prototypes that examined ‘infrastructureless’ networks and alternative communications devices. Specifically, we speculated on the concept of peer-to-peer (p2p) communication and designing devices that communicate from device to device. If anywhere, such alternatives would not be found within the ways of making in the West, where products adhere to strict standards, regulations and pre-conceived uses. As part of our study, we saw the need to physically visit the sites of production where different modes of production are commonplace.

So as a semi-naive point of departure, the goal of the trip was to manufacture a phone. Naive because obviously, we wouldn’t accomplish that. Semi-naive because we KNEW we wouldn’t accomplish that, but we didn’t yet know why. At the same time, we understood that posing as a start-up would (literally) open doors, show new paths to deal with the subject in a more informed way, and, give us a sense on how communication technology is produced, distributed across the world and eventually recycled.

To frame our investigation, we borrowed a concept used in social geography known as ‘The Blue Banana’. It refers to a shape that emerges if one were to take a blue marker and highlight an area on the map of Europe which covers the highest concentrations of people, money, and industry. The resulting elliptical, banana-like shape would then stretch from England through Western Germany, all the way to Northern Italy. Loosely following the shape of the river Rhine, if that river would extend from Venice to Manchester. In the area one would find major cities such as London, Amsterdam, Rotterdam, The Ruhr metropoles, Frankfurt am Main, Munich, Milan, and Venice.

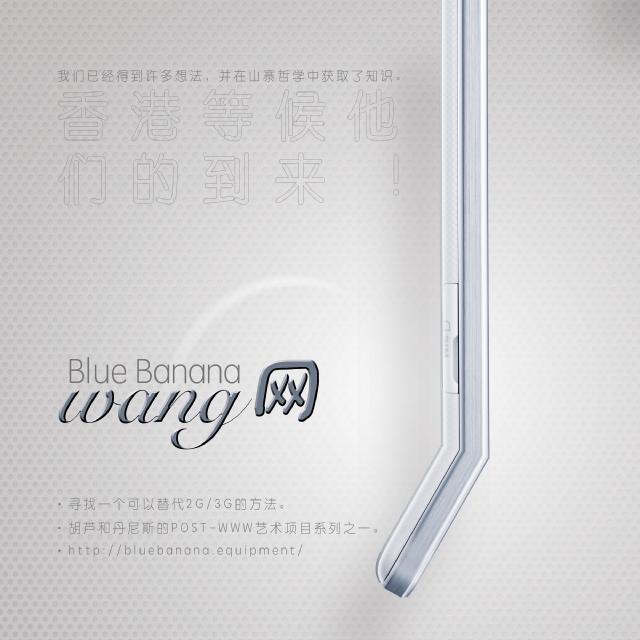

For us, there was more to the concept of The Blue Banana than just a curiosity. We used it to direct our focus on p2p infrastructureless networks, since the area described by the blue banana would also afford the necessary population density for said p2p network(s). At the same time The Blue Banana has a peculiar quality to it, which became a guiding element for the visual design. Dreaming up a phone that somehow worked differently, but also looked the part.

What would make The Blue Banana Phone different is, foremost, a different appearance. The Blue Banana could aesthetically contrast the ubiquitous black box rectangles that constitute 99% of mobile phone designs. In addition, The Blue Banana could invert the traditional telecommunication structure and instead of relying on the standard ‘cell’ network service provider, it could have its type of wireless transmission. Perhaps, something as simple as a walkie-talkie embedded into the device so that we could use it for our transmission standards. After drawing some initial sketches, we began to search for components and parts that could form the basis to re-configure a mobile phone into a Blue Banana communication device. Specifically, we focused on www.alibaba.com, the popular online portal that connects Western techno-consumer desires with Eastern manufacturing and which is valued at 189 Billion USD.

On www.alibaba.com, we stumbled upon a range of companies that produce so called ‘rugged’ phones. These phones are ‘military grade’, heavy duty and water/shock/dust proof and seem to be ‘inspired’ by the ‘Caterpillar’ rugged phones2. To us, these phones were interesting because they had a ‘walkie-talkie’ functionality, in the form of an extra, general purpose, radio transceiver. These products are shanzhai (山寨), a term which, here in the West, evokes nightmares of low-quality fake iPhones. Increasingly, however, scholars from the region are starting to view the style of production linked to shanzhai as a de-facto open-source means of making hardware. This attitude towards production, that involves a common disregard of intellectual property and regulation, leads to fast-paced collaboration and countless designs, each one mimicking and bettering another with endless improvements and new features. Even when concepts are being copied or ‘borrowed’ for new designs, inventive (novelty) features are often added. In the case of the shanzhai rugged phones, the innovation on the original is the addition of the extra radio transceiver.

This distinction between mere copying and adding to the original design is also described by Andrew “Bunnie” Huang, an American hacker with a Chinese background who compares shanzhai production to mash-up culture on the web3:

Their ability to not just copy, but to innovate and riff off designs is very significant. They are doing to hardware what the web did for rip/mix/burn or mashup compilations. The Ferrari toy car meets mobile phone, or the watch mixed with a phone (complete with camera!) are good examples of mashup: they are not a copies of any single idea but they mix IP [Intellectual Property] from multiple sources to create a new heterogeneous composition, such that the original source material is still distinctly recognizable in the final product.

This gives rise to products unseen in the West, in part because this represents a non-western mode of production, in part because these products are not oriented towards Western markets.

To plan our trip, we began eagerly contacting some of these companies as potential customers looking to develop a prototype, to see if we could arrange appointments for factory visits. After many polite dismissals, we eventually managed to arrange a factory visit with the Swell Technology Company (“So Well life”)4. Excited about the prospects of shanzhai as an inspiration for technology that is ‘weirded’ and breaks conventions, we planned to visit electronic markets in both Hong Kong and Shenzhen to gather components to build our devices. At the same time, we were on the lookout for potential collaborators; institutions, hacker spaces, collectives, and individuals who would be interested in helping or facilitating this trip. At the very least, to assist us with the language barrier.

Like so many clueless and stingy (or, shall we say, cost-aware) Western travellers, we ended up booking a ‘room’ in the Chung King Mansions. The Mansions are a group of five 17-storey buildings which house many guest rooms and are situated at the centre of the Kowloon area5, surrounded by fancy stores and malls. These tiny guest rooms all have names designed to appeal to Western travellers, such as ‘The Germany Hostel’, ‘Canadian Hostel’ and we ended up staying in the comfort of the ‘Holland Guest House’. Upon arrival, when entering the slightly daunting mall that covers the first two floors of the building, we immediately noticed many small stores selling various mobile phones and other electronics. Once we found our way to the room, probably like so many other Western travellers, we felt a relief to have escaped the cacophony of market traders downstairs and found ourselves anticipating what the building had in store for us.

After finding our feet, we discovered that, by sheer coincidence, we ended up in a very interesting spot. The anthropologist Gordon Mathews has researched and published extensively on the Chung King Mansions, describing the people that live and work there and the role the building plays in the global technology trade. He considers Chung King Mansions as the hub of ’low-end globalization’. Globalization not at the hands of multinational companies, but rather “[…] globalization done by individual traders carrying goods in their suitcases back and forth from their home countries. That’s the dominant form of globalization here and that’s how globalization works for 70 percent of the world’s people.” Furthermore, Mathews estimates that in 2008 “up to 20 percent of the mobile phones recently in use in sub-Saharan Africa had passed through the building at some point.”6.

At the time, these phones must have been the so-called shanzhai phones. Now we would mostly find the familiar black rectangles and iPhones. Probably because “many of the phones sold today are 14-day phones: phones which were returned by European customers within 14 days of purchase, which retailers buy at a discount and sell on.”7.

To Dutch travellers like ourselves, another aspect of ’low-end globalization’ became apparent when we frequently encountered Dutch powdered-milk formula in many stalls throughout Hong Kong. A considerable amount of this formula is bought by Chinese individuals living in the Netherlands, who independently export Dutch powdered milk to Hong Kong. This kind of informal trade occurs alongside traditional business-to-business exports. These individuals are known to move from supermarket to supermarket purchasing the powdered formula, leaving empty shelves in Dutch supermarkets as a consequence. In Hong Kong, the milk is then sold at a substantial profit to Chinese citizens from mainland China, who, because of food safety concerns, distrust locally produced powdered formula. Dutch supermarkets have noticed the trend and subsequently implemented restrictions on how many items one can buy, sometimes only imposing this limit to Chinese customers.

Hong Kong has changed quite a bit since one of us last visited in 2011, or, perhaps, it wasn’t Hong Kong that changed, but the goods on offer in Sham Shui Po (Hong Kong’s infamous electronics district). In our search for strange, non-standard electronics that used to be widely available, we found only a few. Our techno-orientalist hopes and expectations for obscure and uncommon electronics weren’t met, as we saw so many of the familiar black rectangles, but in larger quantities. One of the reasons for this, could be that as growing wages in China have created an expanding middle class, the Chinese no longer look for the fakes, as they can increasingly afford and purchase the real thing. Another explanation of this phenomenon can be found in a paper by Lindtner, Greenspan and Li on the development of Shanzhai and Maker culture in which they argue that shanzhai isn’t gone, it just became more ‘mature’ and professionalized, oriented less towards niche markets and more towards main stream markets. Take, for example, Xiaomi, a manufacturer with a shanzhai characteristics that has now become a large multinational company that specializes in ’normalized’ devices, uses professional branding and is no longer associated with shanzhai8. When it comes to mobile phones, shanzhai items have become increasingly slick, professional and visually stylized. It becomes difficult to distinguish a shanzhai from a regular device, since both use the same visual language. However, there are still many curious items and products to be found, such as USB to TRRS connectors, rearview mirrors with integrated android devices and brightly coloured powerbanks.

Ever since Andrew “bunnie” Huang and others based in Asia with resonance in the West, started to focused their attention on it 3 the Huaqiangbei (华强北) district has become somewhat legendary for the ‘maker culture’. Lindtner, Greenspan, Li in their paper 8 describe the ecosystem of companies and start-up incubator programs that have sprung up in Shenzhen specifically to make the area accessible to Westerners. ‘Seeed Studio’, a hardware manufacturer that also works to make the Huaqiangbei district popular and accessible for startups and makers, has even published a map of the area 9. Additionally, there are numerous ‘accelerator’ programs based in the city. These programs produce hardware start-ups, complete with branding and kickstarter campaigns, and backed with ambitious venture capital. Those products that made it, you’ve probably heard of, many, however, diffuse into vapourware.

The Huaqiangbei area consists mostly of interconnected malls and multi-storey markets populated by a massive amount of tiny stalls. Instead of finding only retailers for neatly packaged, similar looking products, we found markets where any imaginable electronic item can be found and where devices are sold in various states of (dis)assembly10.

The markets of Huaqiangbei are an ecosystem that encapsulates technological production, consumption, and reclamation and where one can witness the entire life-cycle of a technological product in a single shopping mall. One floor functions as a distributed assembly plant and another as a disassembly and recycling plant. From big to small, each mall also seems to have has its own speciality; from selling stacks of complete devices, to repairing, customizing or offering vast amounts of individual parts. The ground floors of each market seemed more focused on retail for consumers and function as a sort of interface to the floors above street-level. When asking for certain components, or a specific model, we were often directed to a company located on the top-floors that would act as the supplier to the stall on the ground floor.

During our stay in Hong Kong, we were told that, even in Shenzhen, the trade and manufacturing of shanzhai devices was declining, and consequently, we were unable to find as many as we expected. One of the causes of this decline, in addition to the rise of the middle classes in China and the professionalization of shanzhai manufacturing, was the police force cracking down on fake or replica products. The devices we found were mostly ‘dummy’ show-models, non-functional empty plastic cases, used for display purposes before being able to buy the real-fake thing.

The shanzai phones we did find, however, catered to a highly specific niche market. Phones with four SIM Card slots, extra large batteries doubling up as powerbanks or solar-powered rugged phones are all clearly intended for very specific use cases. Others, designed as cigarette packs, were directly related to Chinese smoking culture (“you are what you smoke”) 11 and offer a more healthy alternative to an actual pack of cigarettes, as a gift to improve your ‘guanxi’ 12.

The blurring of lines between obvious shanzhai products and more familiar looking ‘Western’ products is not so strange considering that the majority of electronics available in the West are produced in the Shenzhen area. For the shanzhai manufacturers to compete with the likes of FoxConn, the contract manufacturer for Apple, which produces 540,000 iPhones a day 13, there is no other way than to actively share their knowledge and materials among rival producers and designers 8. In the world of Shanzhai, there is no open-source, there is no closed source. These distinctions are irrelevant in a culture that hinges on competitive market advantage.

One company that produces innovative shanzhai is Swell Technology, who were nice enough to give us a tour of one of their facilities. We arranged to be picked up by one of their representatives in the expensive Sheraton hotel lobby, in the centre of the Shenzhen business district, even though we were staying in a very cheap hotel in Dongmen. This representative drove us to the factory, located outside the city in the more hilly north-east of Shenzhen (the literal translation of shanzai is ‘mountain stronghold’). Upon arrival, our roles as vapour merchants was underlined by the giant LED sign above the company’s reception desk welcoming our arrival. The visit to the Swell factory became an elaborate performance. Both us and the representatives from SWELL were actors and audience at the same time. We were out-staged by a well-rehearsed tour of the facilities. As we became the audience disguised in mandatory pink anti-static clothes, we were led around an expansive warehouse full of vacant and empty assembly lines. Dutifully, we purchased some factory samples, in the hopes of being able to write our own software for the extra radio transceiver in the phone. While going through the company’s catalogue of (unbranded) phones, the mechanics of the economy that we were participating in became clearer. We, the interested buyers, were presented with a catalogue of basic hardware models (gōng bǎn, 公板, ‘public (circuit) boards’)14 which can be modified for your requirements (gōng mó, 公模, ‘public case’)1415. Custom brand names, logo, packaging colours, materials anything you want, with a minimum order of around 300 pieces. This is where brand-new products are custom-made from re-assembled parts, and anyone can leave with a fully configured product for wholesale prices.

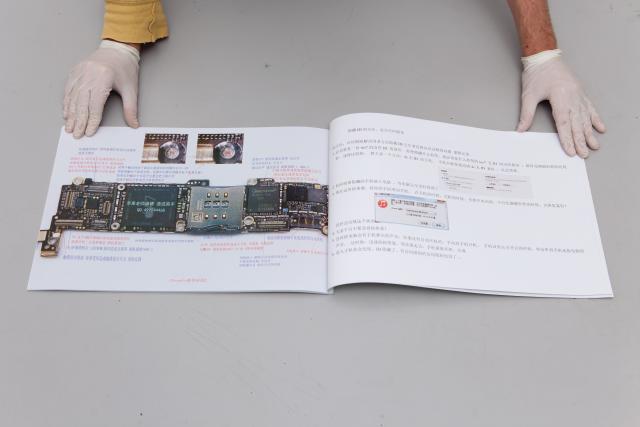

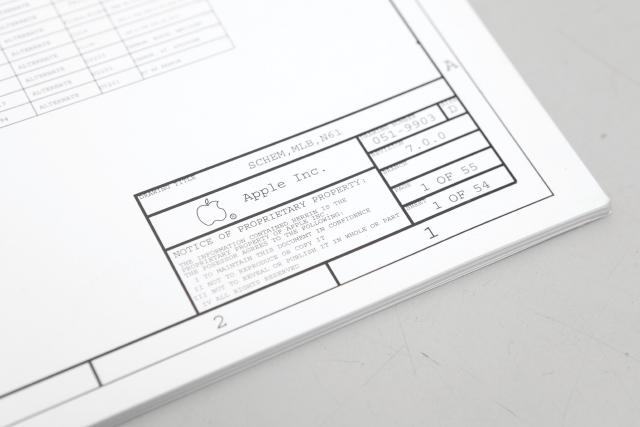

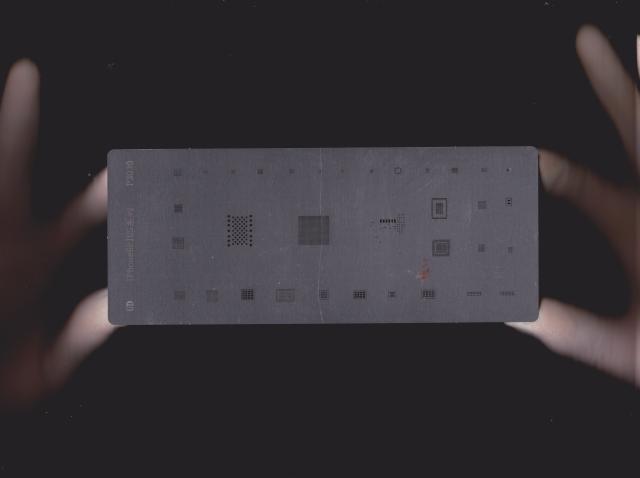

The common attitude towards sharing and collaborating within the production ecosystem is not limited to niche devices. It is also applied to the ins and outs of mainstream brands such as Apple and Samsung. Everything from spare screens (in flavours “original”, “high copy”, “good copy”) to complete electronic schematics, parts lists (“open bill of materials”3), solder stencils and reverse engineered manuals are available for public use. Mainstream devices, such as the iPhone, are arguably better documented in Huaqiangbei than in the West. However, this culture of openness is distinctly different from the open-source software culture familiar to us in the West, despite it being frequently compared to or even conflated with. While we fruitlessly searched for the ‘open-source’ boards known as ‘gōng bǎn’ in the markets of Huaqiangbei, it became obvious that we were not in the right place nor did we have access to the communities and subcultures that would carry these ‘open’ boards. While it is easy to recognize similar patterns between open-source Maker movements and Chinese electronic maker communities, the culture and ideology of making and designing technology distinct from anything we were accustomed to. This was made explicitly clear after we purchased our radio phones from the SWELL factory, and we witnessed the company representative’s confusion and distrust towards our continuous questions regarding technical documentation of the hardware. Becoming part of this ‘open’ ecosystem involves a long process of building trust and reputation, in addition to understanding the specific social and cultural dynamics of the area. This issue of earning trust and gaining access to gōng bǎn and to connections to produce your own devices, has given rise to numerous consultancy companies assisting connections between foreign investors and Chinese manufacturers.

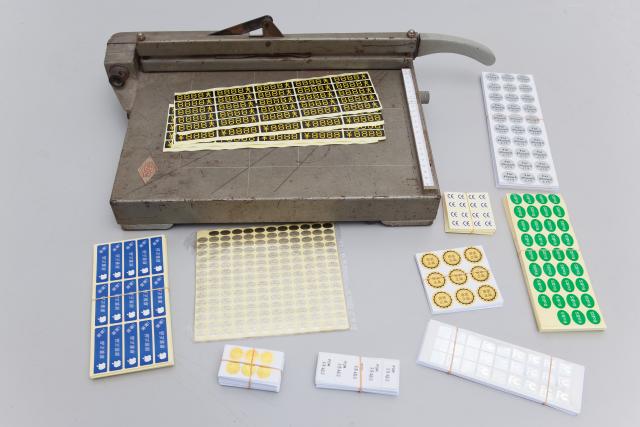

Most devices produced in the Special Economic Zone (SEZ) of Shenzhen are designed for export to foreign investors who, encouraged by special tax incentives[14], outsource a large portion of their production (and design) to the region. That also requires a supply of stickers for many recognizable official looking certifications like CE, FCC and Rohs, which can also be found on the markets of Huaqiangbei. But there is another market relying on these holographic beauties, which is the one of shanzai products and accessories. After production, most goods, including iPhones, are directly shipped to Hong Kong which is the starting point for international trade. There is a lucrative market for these Hong Kong iPhones in China because they can be bought tax-free. This creates an informal circulation, not too dissimilar to the milk formula from Dutch supermarkets, where phones are first exported to Hong Kong, then bought by mainland Chinese, unboxed (to save space) and smuggled back into mainland China, where the ‘Hong Kong iPhones’ are sold at a lower price. According to the architect Liam Young, this results in a lively market for the production of shanzhai iPhone boxes. While we haven’t seen the boxes, we have seen and collected all the stickers that would adorn these cardboard boxes16.

We concluded our journey with an evening of presentations at the house of one of our contacts, Li Weiwei. She spent some days with us in Shenzhen helping with translation and showing us around. She invited us, along with some other artists, to talk about each other’s work. Most of the Chinese people present were Western-educated, working either as artists or in the broader cultural sector. That evening, we had a conversation about the ‘culture’ of Shenzhen, which many participants found was non-existent. This sentiment echoed other voices we heard during our trip. The city of Shenzhen itself, being only 30 years old, was perceived by its inhabitants as only a site of business, and not one of culture. Culture is still regarded as something linked to history and tradition, the 2000-year-old neighbouring city of Guanghzhou being a case in point. We would argue to the others that shanzhai represents one of Shenzhen’s own distinct cultures, akin to other bricolage (‘diy’) cultures but even pushing it into (industrial) design cultures. This idea, however, was rejected by the group, shanzhai still bearing the negative connotations of inferior quality and lack of originality, in relation to Western products.

One site where one can witness tradition mixing with the new cultural production is in the so called ‘Joss paper’. These paper craft artefacts are burnt as offerings in small shrines dedicated to deities and the recently deceased. Increasingly, however, Joss papers are made to represent contemporary items of value such as money, credit cards, houses, cars, and electronic consumer goods. These paper models have moved with the times, to replicate consumer desires that are then offered to the spirits of the past. They represent items one hopes to attain during life, but which one receives only in the spirit world. In light of our trip, the Blue Banana phone reached a similar conclusion, becoming an effigy representing a set of desires and ideas on technology that materialized into nothing more than a few souvenirs from the vapour trail.

-

“Vaporware”. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vaporware, retrieved 10 March 2016. ↩︎

-

“CAT rugged phones”. http://www.catphones.com/en-gb, retrieved 10 March 2016. ↩︎

-

“Tech Trend: Shanzhai”. Bunnie’s Blog. http://www.bunniestudios.com/blog/?p=284, retrieved 10 March 2016. ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

-

“Shenzhen Swell Technology”. http://www.cnswell.com, retrieved 10 March 2016. ↩︎

-

“Chung King Mansions”. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chungking_Mansions, retrieved 10 March 2016. ↩︎

-

“Inside Chungking Mansions with expert Gordon Mathews”. CNN. http://travel.cnn.com/hong-kong/life/inside-chungking-mansions-expert-gordon-mathews-098440/ , retrieved 10 March 2016. ↩︎

-

“Chungking Mansions: Inside Hong Kong’s favourite ‘ghetto’”. BBC. http://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-24015987, retrieved 10 March 2016. ↩︎

-

“Designed in Shenzhen: Shanzhai manufacturing and maker entrepreneurs” Lindtner, Greenspan, Li. http://www.silvialindtner.com/s/Lindtner-Greenspan-Li_Designed-in-Shenzhen_2015.pdf, retrieved, March 10 2016. ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

-

“Shenzhen Map For Makers” Seeedstudio. http://www.seeedstudio.com/document/pdf/Shenzhen%20Map%20for%20Makers.pdf, retrieved 10 March 2016. ↩︎

-

For images or the area as well as more work exploring it and the informal markets around it see: https://dennisdebel.nl/2017/2019-Navigating_HQB/ and de Bel, D. (2020). The Ghosts of Shenzhen. In Realtime: Making digital China (First edition, pp. 113–125). EPFL Press. https://www.epflpress.org/produit/968/9782889153459/realtime-making-digital-china ↩︎

-

“China’s cigarette culture” China Daily. http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/china/2014-01/09/content_17226897.htm, retrieved March 10 2016. ↩︎

-

“Smoking in China” Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Smoking_in_China, retrieved March 10 2016. ↩︎

-

“iPhone 6 production by the numbers: 100 production lines, 200k workers, 540k phones a day”. http://9to5mac.com/2014/09/17/iphone-6-production-by-the-numbers-100-production-lines-200k-workers-540k-phones-a-day/, retrieved, March 9 2016. ↩︎

-

“Shanghai and Disruptive Innovation” Anna Greenspan for The Globalist. http://www.theglobalist.com/shanghai-and-disruptive-innovation/ retrieved 10 March 2016. ↩︎ ↩︎

-

Chinese translation by Nan Wang. ↩︎

-

“The Geologic Imagination”. Interview with Liam Young of Unknown Fields Division, 2015 Sonic Acts Press. ↩︎